소구상체(Orbicules)의 계통분류학적 검토

The phylogenetic potential of orbicules in angiosperms

Article information

Abstract

적요

Orbicule(소구상체)의 분포를 확인하기 위하여 꿀풀과에 속하는 6속 11분류군과 마편초과 3속 4분류 군의 약벽을 주사전자현미경(scanning electron microscope)을 이용하여 관찰하였으며, 문헌조사를 통해 현화 식물 내 소구상체의 분포가 갖는 계통분류학적 유용성 및 융단조직 유형과의 관련성에 대해 검토하였다. 그 결과 꿀풀과 분류군들에서는 모두 소구상체가 관찰되지 않았고, 마편초과 분류군들에서는 평균 1 μm 이하, 구형의 소구상체들이 조밀하게 분포하는 것을 살펴볼 수 있었다. 이와 같은 과 수준에서 일관성 있는 소구상 체의 분포 특징은 현화식물 전체 orbicules에 대해 조사된 150과 중 123과와 일치하는 것으로 소구상체의 분 포 유형 자체가 분류학적 예견적 가치를 지니는 것으로 나타났다. 또한, 융단조직 유형이 확인된 분류군들 중 분비형 융단조직을 갖는 분류군의 약 84%에서 소구상체가 나타나고, 아메바형 융단조직을 갖는 분류군의 약 80%은 소구상체가 나타나지 않는 것으로 조사되어 소구상체의 발달이 융단조직 유형과 밀접한 관련이 있는 것으로 조사되었다. 하지만, 현재까지 수행된 소구상체 연구는 현화식물 전체 416과들 중 150과에 제한 되어 있고, 이들 분류군들 중 융단조직 유형은 92과에서만 알려져 있어 소구상체의 기능 및 융단조직 유형과 의 유연관계를 규명하기 위해서는 보다 광범위한 분류군을 대상으로 한 연구가 필요한 것으로 나타났다.

Trans Abstract

The distribution of orbicules was investigated for eleven taxa of six genera in Lamiaceae and four taxa of three genera in Verbenaceae using scanning electron microscopy. A literature survey to evaluate the phylogenetic potential of the orbicules and their possible correlations with tapetum types was also conducted. The orbicules are consistently absent in all investigated taxa of Lamiaceae, while small orbicules of an average size of less than 1 μm are densely distributed in Verbenaceae. In fact, orbicules appear consistently in 123 of 150 angiosperm families when investigated in at least one species. Thus, the distribution patterns of orbicules could be a useful diagnostic character in angiosperms. In addition, orbicules occur in 84% taxa of the secretory tapetum type, while they are commonly absent in the amoeboid tapetum type (ca. 80%). The presence of orbicules may be correlated with the secretory tapetum type. However, the study of orbicules is restricted in 150 families and the tapetum type within these families can be applied for 92 families out of a total of 416 angiosperm families. Thus, further investigation of orbicules is necessary in extended taxa to address the questions pertaining to orbicules.

Pollen morphological traits have been considered as useful diagnostic characters, since they often provide important clues to identify plant species and infer their evolutionary history. Recently, using electron microscope the micromorphological features on pollen wall reflect its phylogenetic potential (Moon et al., 2008a). The pollen exine consists of sporopollenin, a complex and highly resistant biopolymer which protect pollen grains from mechanical damage or degradations, thus pollen grains remain well preserved in fossils (Erdtman, 1960).

Orbicules (or Ubisch body) are small, granular structures that are found in mature anthers as a layer of tiny particles lining in the inner locule wall and are composed of sporopollenin, like the pollen exine (El-Ghazaly, 1999; Huysmans et al., 2000; Galati, 2003). Orbicules were observed for the first time by a Russian scholar Rosanoff (1865). Since then, much attention has been paid to these structures and palynological studies have been intensively conducted, coupled with endothecium structure, pollen development and sporopollenin synthesis (Huysmans et al., 1998, reference therein). Recent studies address that the distribution, size and shape of orbicules has phylogenetic significance, so orbicules are drawing keen attention in that they could be the characters to reflect the phylogenetic correlation of angiosperms, as well as pollen morphological features (Moon et al., 2008a; Huysmans et al., 2010; Verstraete et al, 2011; Song et al., 2016).

Orbicules develop simultaneously with the pollen grains and are acellular tiny particles that generally observed on the innermost tangential and/or radial walls of secretory tapetum type (=parietal or glandular tapetum type) (Kosmath, 1927; Ubisch, 1927). Secretory tapetum type is a basic tapetum that can be found in angiosperms, along with amoeboid tapetum type (=plasmodial tapetum type) whose cell wall is disrupted and cytoplasm is released to anther locule. Universally, the secretory type occurs in the existing basal angiosperms, the majority of fossil plant taxa and angiosperm families, thus being regarded as more plesiomorphic type than amoeboid type (Furness and Rudall, 2001). In this context, orbicule development could be a plesiomorphic condition of taxa (Huysmans et al., 2010; Verstraete et al., 2011). However, since orbicules are observed in the taxa with the amoeboid tapetum type such as Abutilon pictum (Gillies ex Hook.) Walp., Acacia conferta, Benth. Beta vulgaris L., Butomus umbellatus L., Canscora alata (Roth) Wall., and Gentiana acaulis L., their correlation with the tapetum type remains unclear (Lombardo and Carraro, 1976; Fernando and Cass, 1994; Huysmans et al., 1998; Strittmatter and Galati, 2000; Vinckier and Smets, 2003; Furness, 2008; Taylor et al., 2008; Verstraete et al., 2014).

Orbicules are readily observable in mature anther and inner locule wall by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Usually they are smaller than 1 μm, but orbicules with a diameter up to 15 μm are reported in Quararibea Aubl. (Nilsson and Robyns, 1974). Generally, orbicules are spherical with a smooth surface (psilate), but diverse shapes such as granulate, echinate, or microperforate are also found depending on taxa. It is noteworthy that in some species the sculpturing pattern of orbicules are similar with sexine ornamentation (Rowley et al., 1959; Hesse, 1986; Huysmans et al., 2000). Recently, intensive studies have been conducted to investigate the presence of orbicules and their morphological diversity, along with the pollen-morphology research (Moon et al., 2008b; Song et al., 2016, 2017a, 2017b). Nevertheless, there are very few data on orbicule research in Korea, except for some studies on orbicule development associated with the pollen development (Jeong, 2009). In angiosperm as a whole the data on orbicules are rather restricted.

Thus, here I would add new data of orbicules in taxa of Lamiaceae and Verbenaceae to evaluate its phylogenetic potential. In addition, the literature survey is also conducted to check possible correlation between orbicule existence and tapetum type.

Materials and Methods

To investigate the distribution and characteristics of orbicules two families were selected based on previous studies (Moon et al., 2008a, 2008b, 2008c). Orbicules of 15 taxa were observed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM); 11 taxa of 6 genera in Lamiaceae and 4 taxa of 3 genera in Verbenaceae. The literature search encompassed the data screened until 2012 (Verstraete et al., 2014) and 19 additional papers published until September 2017 (5,154 taxa of 58 genera in 12 families; Appendix 1). Based on the results of this study, I attempted to evaluate the orbicule distribution in angiosperms and its possible correlation with tapetum type.

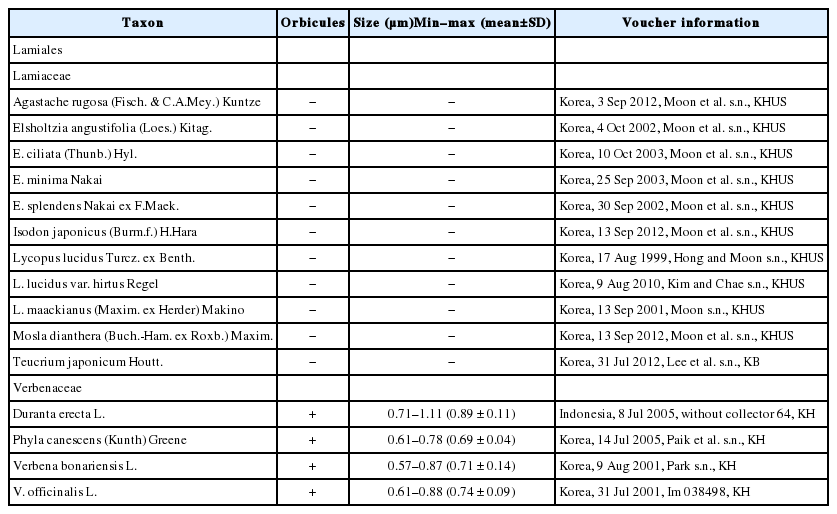

For SEM observation of orbicules, fully matured anthers were collected from herbarium specimen (Table 1). Dried anthers were rehydrated for at least one day in a commercially available wetting agent Agepon or Photo Flo (1:200 in distilled water). Following the dehydration procedures by a graded ethanol series (30, 50, 70, 90, and 100%) twice with 10 min incubation for each step, the completely dehydrated anthers were critical point dried (SPI-13200J-AB; SPI Supplies, West Chester, PA, USA) using CO2 gas to optimally conserve their natural size and shape. Dried anthers were fixed to aluminum stubs with double adhesive carbon tape for observing the inner locule wall. Stubs were sputter coated with platinum (ionsputter coater; JFC-1100; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Orbicules were observed using a SEM (JEOL JSM-6360) or a Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FE-SEM, S-4700; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) at a working distance of 10–15 mm and an accelerating voltage of 5–10 kV. Once orbicules were observed, the size measurements of at least 30 orbicules were ascertained using a microscope with Macnification 2.0 (Orbicule, Leuven, Belgium). The results are presented in Table 1, together with orbicule distribution and voucher specimen information.

The orbicule existence data of present study and their size variation with voucher information. +, orbicule presence; −, absence.

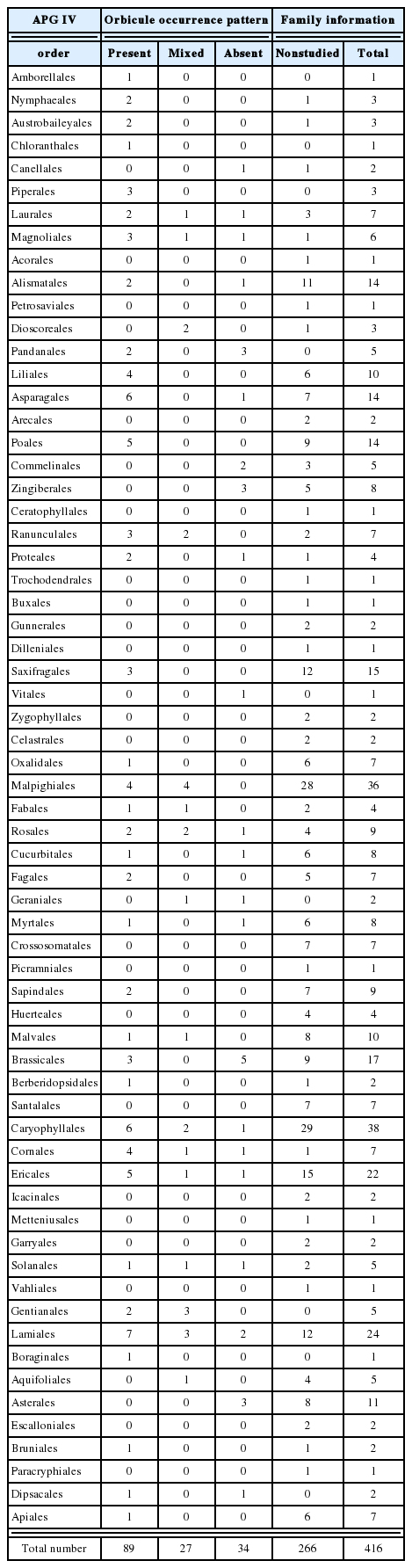

The scientific literatures under “orbicules or ubisch body” in the title or text were screened for information of orbicules from 2012 to September 2017, aiming to investigate the possible correlations between distribution of orbicules and tapetum type in angiosperms. Additional 19 papers (including previously omitted papers; Rao, 1954 and Nilsson and Robyns, 1974) were combined to the data published by Verstraete et al. (2014: papers published until 2012) and the results of this study (Table 1, Appendix 1). The occurrence data of orbicules were re-arranged based on APG IV system with 416 families of 64 orders (Angiosperm Phylogeny Group, 2016; Table 2). In addition, the tapetum type in taxa with orbicule data was investigated to evaluate the relationship between orbicules and tapetum type (Table 3).

Occurrence patterns of orbicules based on APG IV (2016).

Results and Discussion

Orbicules

Rosanoff (1865) observed minute granules of sporopollenin, called orbicules or Ubisch bodies, in Mimosa taxa of Fabaceae. In 1962, a palynologist Rowley introduced the term “Ubisch bodies” commemorating the contribution of Gerta von Ubisch (1882–1965) who published a list of taxa with or without orbicules, but currently, the term “orbicules” has been used more generally and widely (Huysman et al., 1998; Verstraete et al., 2014). Orbicules (or Ubisch body) are small particles of sporopollenin that are found in mature anthers as a layer of tiny particles lining the inner locule wall that surrounds developing pollen grains. Usually orbicules are tiny, spherical granules with individually independent shapes. Based on these features of orbicules, this paper suggests their Korean term as ‘So-gu-sang-che (소구상체)’ (Yamada, 1987; Chung and Kuo, 2005; Moon, 2008).

Orbicule characteristics

Usually orbicules are observable when the pollen develops in the secretory tapetum, and fully matured orbicules are present in anther and inner locule wall. The existence of orbicules can be easily identified in mature anther and inner locule wall (Fig. 1A, B). If orbicules are absent, the surface of the inner locule wall is smooth and in the presence of orbicules, lots of orbicules are evenly distributed on the surface of the inner locule wall (Fig. 1C–H). Previous studies indicate that orbicules are most variable in size, shape and surface sculpturing of taxa. The surface sculpturing of orbicules is correlated with sexine ornamentation of the pollen (Rowley et al., 1959; Hesse, 1986; Huysmans et al., 2000).

Scanning electron microscopy micrographs of anther and inner locule wall. A, B. Fully matured open anther. A. Elsholtzia ciliata. B. Verbena bonariensis. C, D. Inner locule wall without orbicules. C. Agastache rugose. D. Elsholtzia angustifolia. E–H. Inner locule wall with orbicules. E. Verbena bonariensis. F. Verbena officinalis. G. Duranta erecta. H. Phyla canescens.

The results of this study show that the orbicules are consistently absent in 11 taxa of Lamiaceae and small, spherical orbicules (the average size of less than 1 μm) are densely distributed throughout the anther and inner locule wall in 4 taxa of Verbenaceae (Fig. 1E–H, Table 1). In Lamiaceae, orbicules are present in some taxa of Chloantheae (Raj and El-Ghazaly, 1987), but they are absent in Mentheae, Galeopsis L., Scutellaria L., and Stachys Tourn. ex. L. (Moon et al., 2008a, 2008b, 2008c; Verstraete et al., 2014). In fact, orbicule distribution was intensively studied in Mentheae which showed consistently absence of orbicules in all studied taxa (150 species from 61 genera; Moon et al., 2008a, 2008b, 2008c). In the present study, orbicules are absent in Elsholtzia Willd. and Mosla (Benth.) Buch.-Ham. ex Maxim. of the tribe Elsholtzieae and Isodon (Benth.) Spach of the tribe Ocimeae. These results suggest that absence of orbicules could be a putative synapomorphic condition in Nepetoideae which consists of three tribes Elsholtzieae, Ocimeae and Mentheae (Moon, 2008).

In Verbenaceae, orbicules are present in all studied taxa with similar shape and size that observed in Junellia thymifolia (Lag.) Moldenke (Moon, 2008). The orbicules of studied taxa are spherical with a psilate surface and the average size is less than 1 μm. However Duranta erecta L. possessed comparatively larger orbicules with over than1 μm in diameter and Phyla canescens (Kunth) Greene has a relatively small orbicules. In addition, two species of Verbena have similar orbicules in diameter (Table 1). According to the phylogenetic analysis within the family with respect to the size variation of orbicules, smaller orbicules occurred in advanced groups (Marx et al., 2010). This result would run counter to Rubiaceae showing the relatively small orbicules as a plesiomorphic character (Verstraete et al., 2011). Therefore, to elucidate the phylogentetic potential of orbicules, further study is necessary to investigate the occurrence of orbicules and their characters in the entire family.

Systematic implication of orbicules and their relationship to tapetum type

In the present study, the additional orbicule data (11 orders, 14 families, 67 genera, 169 taxa) updated the previous data from Verstraete et al. (2014) and this dataset was interpreted with most recent angiosperm phylogeny (Angiosperm Phylogeny Group, 2016). Most findings from this study support the previous studies like distribution patterns of orbicules at order level. The occurrence of orbicules is ascertained in Eupteleaceae and Ochnaceae at the family level for the first time (Appendix 1). Family Rosaceae was reported as a consistent occurrence group of orbicules (Verstraete et al., 2014) but recent studies showed the distribution patterns are varying according to the taxa with consistent trend at generic level (Song et al., 2016, 2017a, 2017b).

According to the APG IV system, all angiosperms split into 64 orders and 416 families (Angiosperm Phylogeny Group, 2016). Of the 416 families, the number of orbicules investigated for at least one species accounted for about 64% of total 150 families, of which 266 families remained uninvestigated (Fig. 2, Table 2). Orbicules observed in the 150 families are extremely restricted to specific taxa, so the systemic significance of orbicules has yet to be fully elucidated due to insufficient data. Notwithstanding this, the consistent tendency about presence or absence of orbicules at family level counts in 123 families, and in 27 families only, the presence and absence of orbicules are both observed between taxa. Among these 27 families, the consistency of orbicules existence appears in 139 of total 147 genera at generic level, while the presence of orbicules differs from the following genera only: Aletris L. (Nartheciaceae), Coptosapelta Korth. (Rubiaceae), Dioscorea Plum. ex. L. (Dioscoreaceae), Gentiana Tourn. ex. L. (Gentianaceae), Ilex L. (Aquifoliaceae), Monodora Dunal. (Annonaceae), Passiflora L. (Passifloraceae), and Ziziphus Mill. (Rhamnaceae). The distribution pattern of orbicules may have a systematically consistent tendency (Santos and Mariath, 1999; Schols et al., 2001, 2003; García et al., 2002; Vinckier and Smets, 2003; Verellen et al., 2004; Furness, 2008, 2011; Merckx et al., 2008; Huysmans et al., 2010; Gotelli et al., 2016).

Modified phylogeny of APG IV from Cole et al. (2017) with proportion data of orbicule occurrence at family level of each order (based on present data and Verstraete et al., 2014; Table 2). Different colors: orange, family with orbicules; blue, family without orbicules; green, family both with and without orbicules; grey, no data available.

Generally, orbicule development has been reported from ANITA group (the earliest diverged grade), the most primitive taxa, even within pteridophytes, gymnosperms and angiosperms. The occurrence of orbicules is believed to reflect the plesiomorphy of taxa. Thus orbicules are suggested as having a correlation with the primitive, secretory tapetum type (Huysmans et al., 1998). The consistent tendency was reported in Rubiaceae (322 taxa of 163 genera) and Annonaceae (46 taxa of 29 genera) which are extensively studied groups in orbicule distribution of angioserms. The presence of orbicules in both families is common in the basal group and restricted to the secretory tapetum type (Huysmans et al., 2010; Verstraete et al., 2011). However, orbicule distribution is ascertained in the taxa with amoeboid tapetum type, such as Abutilon pictum and Modiolastrum malviflorum (Griseb.) K. Schum. of Malavaceae, and Canscora alata, Gentiana acaulis, and Swertia perennis L. of Gentianaceae (Lombardo and Carraro, 1976; Strittmatter and Galati, 2000; Vinckier and Smets, 2003; Galati et al., 2007). The occurrence of orbicules is also observed from the following extremely restricted taxa, with invasive tapetum type as the intermediate form of amoeboid and secretory types: Aechmea diclamydea Baker (Bromeliaceae), Quercus robur L. (Fagaceae), Modiolastrum malvifolium (Griseb.) K. Schum. (Malvaceae) and Vinca rosea L. (Apocynaceae). Thus, more diversified approaches are needed to investigate the correlation between tapetum type and orbicules existence (El-Ghazaly and Nilsson, 1991; Galati 2003; Rowley and Gabarayeva, 2004; Sajo et al., 2005; Galati et al., 2007). As a result, orbicules are present in 240 of 285 taxa with the secretory tapetum type and orbicules are absent in 29 of 36 taxa with the amoeboid tapetum type, indicating a clear tendency between orbicule development and tapetum type (Table 3).

Orbicules-related studies were conducted in about 36% of total angiosperms at family level (accounts for less than 5% of all taxa at species level) and among the taxa whose orbicules were investigated, tapetum type-identified taxa account for about 18% of total taxa. Under such circumstances, further comparative study with expanded taxa is preferentially required to elucidate the systematic significance and evolutionary tendency on the distribution and characteristics of orbicules as well as their relationships with tapetum type.

According to all of the orbicule characteristics studied up to this date, it can be concluded that the presence of orbicules reflects the primitive characteristics of taxa and the occurrence of orbciules represents the consistent characteristics within specific taxa at family level, thereby orbicule distribution might have predictive value in systematics. In particular, since orbicule development is generally common in secretory tapetum and orbicules develops in amoeboid typetum in an extremely restricted manner, further study is warranted to clarify the correlation between tapetum type and orbicules.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Prof. Dr. Suk-Pyo Hong and members of the Lab. of Plant Systematics at Kyung Hee University for their various help. I thank the directors of the following herbaria for permitting the examination of specimens, either through loans or during visits: KB, KH, KHUS. I also thank the editor in chief Prof. Dr. Young-Dong Kim and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, which helped me to improve this paper. This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2016R1D1A1B04934156).

Notes

Conflict of Interest

The author declare that there is no conflict of interest.