Phylogenetic position of Daphne genkwa (Thymelaeaceae) inferred from complete chloroplast data

Article information

Abstract

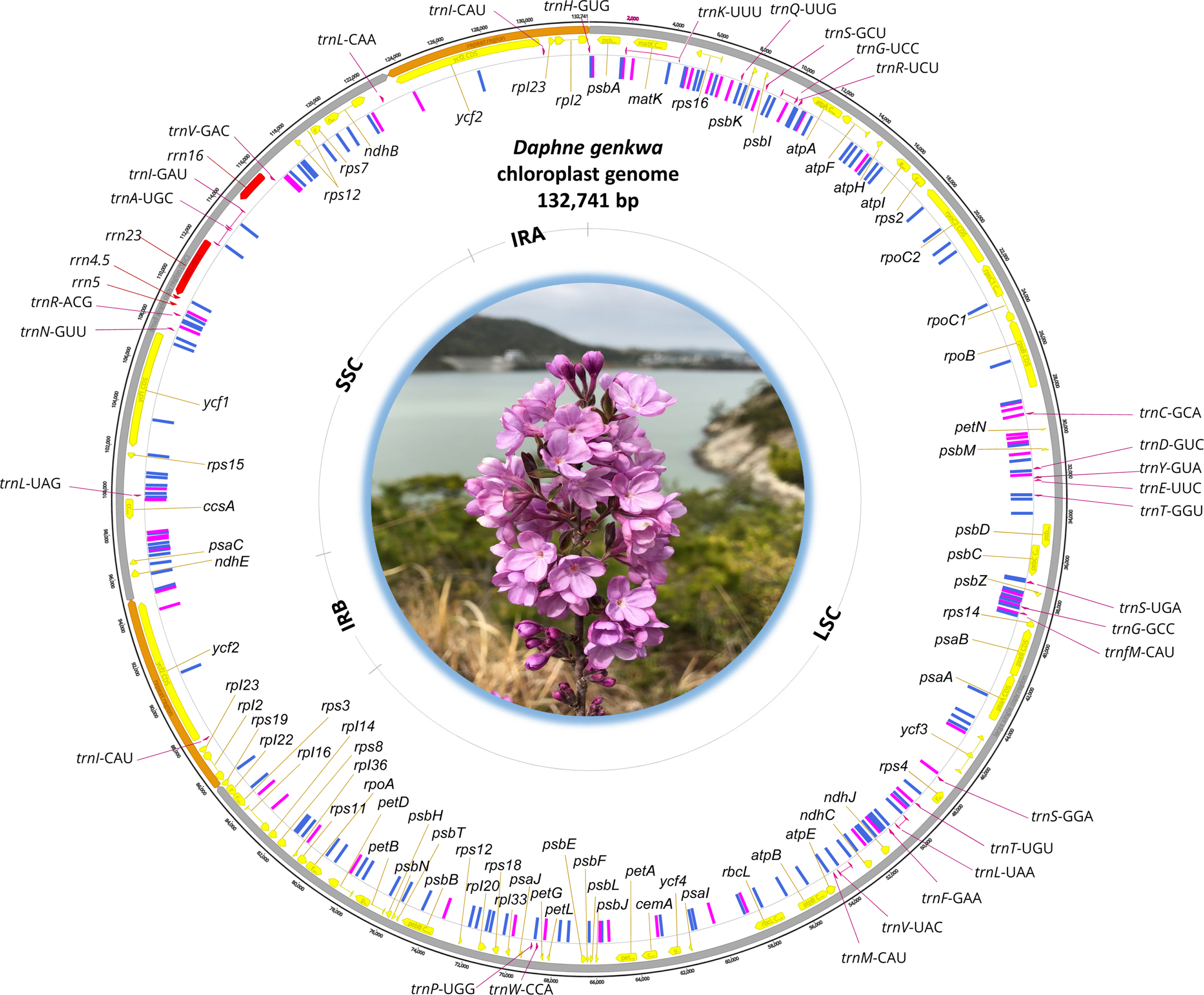

Daphne genkwa (Thymelaeaceae) is a small deciduous shrub widely cultivated as an ornamental. The complete chloroplast genome of this species is presented here. The genome is 132,741 bp long and has four subregions: 85,668 bp of large single-copy and 28,365 bp of small single-copy regions are separated by 9,354 bp of inverted repeat regions with 107 genes (71 protein-coding genes, four rRNAs, and 31 tRNAs) and one pseudogene. The phylogenetic tree shows that D. genkwa is nested within Wikstroemia and is not closely related to other species of Daphne, suggesting that it should be recognized as a species of Wikstroemia.

Daphne genkwa Siebold & Zucc. (Thymelaeaceae) distributed in China, Korea, and Taiwan, is an economically important species given its use as an ornamental shrub (White, 2006). It is characterized by head-like umbellate inflorescence, purple to lilac-blue flowers without a scent, and a cup-shaped disk (Wang et al., 2007; Oh and Hong, 2015). Daphne genkwa is unique in the genus Daphne L. because it has opposite or occasionally alternate leaves and the aforementioned purple to lilac-blue flower color and no fragrance.

Previous studies of Korean Thymelaeaceae based on palynology (Jung and Hong, 2003a) and leaf anatomy (Jung and Hong, 2003b) showed that D. genkwa is more similar to Wikstroemia Endl. than it is to other species of Daphne. Lee and Oh (2017) in their morphological revision of Korean Thymelaeaceae also found that D. genkwa is morphologically similar to Wikstroemia based on the leaf arrangement, pubescence of the leaves, and the ovary shape. The distinction between Daphne and Wikstroemia is problematic as they do not have clear diagnostic characteristics. Some authors, such as Domke (1932), placed D. genkwa in Wikstroemia, while most other botanists recognized it as a species in Daphne (Hamaya, 1955; Ohwi, 1965; Wang et al., 2007; Oh and Hong, 2015). Halda (2001), on the other hand, did not recognize Wikstroemia and merged it into Daphne. A molecular study of Korean Thymelaeaceae (Lee, 2015) showed that D. genkwa is nested within the genus Wikstroemia.

As part of phylogenomic study of Thymelaeaceae, we aimed to determine the complete chloroplast genome of D. genkwa from the Korean plant, evaluate the level of molecular variation of the genome, and infer the phylogenetic position of the species based on the complete chloroplast genome data of Thymelaeaceae.

Materials and Methods

Plant material

We collected D. genkwa in Hwangsan-myeon, Haenam-gun, Jeollanam-do in Korea (34°35′16.16″N, 126°0′0″E). A voucher and isolated DNA was deposited in the herbarium of Daejeon University (TUT, under the voucher number Oh et al. 8085).

DNA extraction and chloroplast genome determination

The genomic DNA was extracted from fresh leaves using a DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Genome sequencing, de novo assembly, and base confirmation were done according to the methods used in previous studies under the environment of the Genome Information System (GeIS; http://geis.infoboss.co.kr/) (Park and Oh, 2020; Park et al., 2020c). Genome annotation was based on the D. genkwa chloroplast genome (NC_045891) using Geneious Prime 2020.2.4 (Biomatters Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand).

Circular map of D. genkwa chloroplast genome was drawn using Geneious Prime 2020.2.4 (Biomatters Ltd.) after adding positions of intraspecific variations identified from both D. genkwa chloroplast genomes.

Phylogenetic analyses and hypothesis test

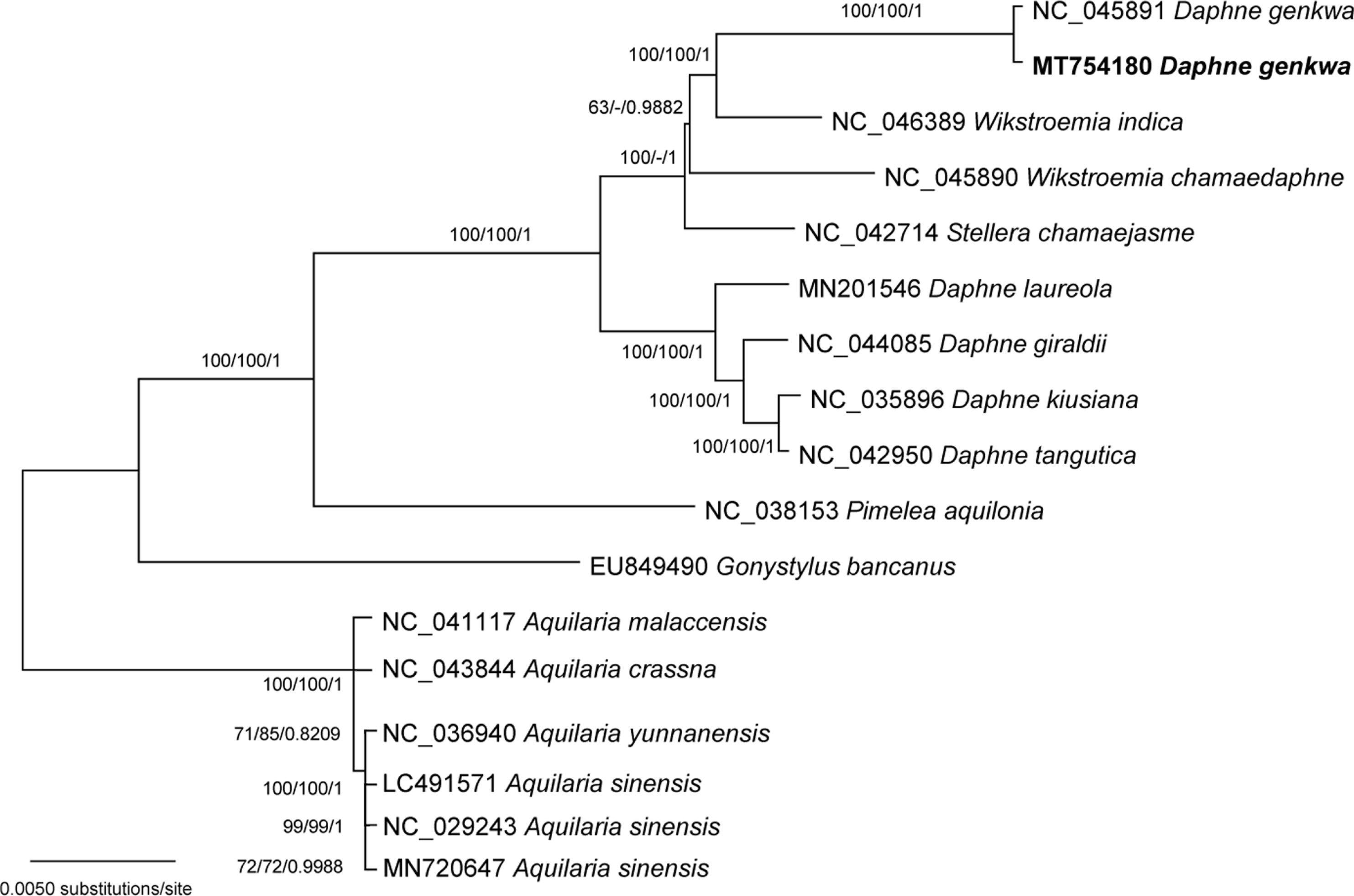

Forty-seven conserved genes from 17 chloroplast genomes including two D. genkwa chloroplasts were used in a phylogenetic analysis using the maximum likelihood (ML), neighbor-joining (NJ), and Bayesian inference (BI) methods. Chloroplast genomes of Aquilaria, that is Aquilaria crassna Pierre ex Lecomte (NC_043844), Aquilaria malaccensis Lam. (NC_041117), Aquilaria sinensis (Lour.) Spreng. (LC491571, MN720647, and NC_029243), and Aquilaria yunnanensis S. C. Huang (NC_036940), were used as outgroups. A heuristic search was conducted with nearest-neighbor interchange branch swapping, the Tamura-Nei model, and uniform rates among sites to construct an ML phylogenetic tree with the 1,000 pseudoreplicate bootstrap options and default values for the other options using MEGA X (Kumar et al., 2018). The NJ tree was generated with the 1,000 pseudoreplicate bootstrap options using MEGA X. The BI tree was constructed using Mr. Bayes 3.2.7a (Ronquist et al., 2012). The GTR model with gamma rates was used as a molecular model. A Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm was employed for 1,000,000 generations, sampling trees every 200 generations, with four chains running simultaneously. Trees from the first 100,000 generations were discarded as burn-in.

A specific phylogenetic hypothesis of a monophyly of Daphne was tested using the Shimodaira-Hasegawa (SH) test (Shimodaira and Hasegawa, 1999) and Approximately Unbiased (AU) test (Shimodaira, 2002), as implemented in PAUP* (Swofford, 2002). Maximum parsimony (MP) trees were generated constraining a topology, in which D. genkwa is placed to be a sister to the rest of Daphne. Heuristic search option was used with 100 replicates of random sequence additions with tree bisection-reconnection branch swapping, with all of the best trees saved at each step (MulTrees). The constrained MP trees were evaluated with the original ML tree without the constraint. For the SH and AU tests, 10,000 bootstrap replicates were re-sampled using the re-estimated log likelihood (RELL) method.

Results and Discussion

The chloroplast genome of D. genkwa (Fig. 1) is 132,741 bp (GC ratio is 36.3%) and has four subregions: 85,668 bp of large single copy (34.8%) and 28,365 bp of small single copy (39.6%) regions are separated by 9,354 bp of an inverted repeat (IR; 38.5%). It contains 107 genes (71 protein-coding genes, four rRNAs, and 31 tRNAs) and one pseudogene (accD); four genes (three protein-coding genes and one tRNA) are duplicated in IR regions. The lengths of the IR regions of both D. genkwa chloroplasts are the shortest among the Thymelaeaceae chloroplasts known thus far (Fig. 1), which contributes to the short length of the corresponding chloroplasts. Interestingly, the IR of Wikstroemia indica (L.) C. A. Mey is relatively short in comparison to those of Wikstroemia chamaedaphne (Bunge) Meisn. and the four Daphne chloroplasts. The chloroplast genome of D. genkwa in this study is deposited in NCBI GenBank with the accession number of MT754180.

The circular map of Daphne genkwa chloroplast determined in this study. Specific sites differed from the Chinese sample (NC_045891) are indicated inside of the circular map: SNP with a blue rectangular bar and indel with a magenta rectangular bar. Photograph of D. genkwa taken by Sang-Hun Oh is inserted at the center of the chloroplast map.

Based on pairwise alignment of two chloroplast genomes of D. genkwa, one from our Korean material and the other from China (NC_045891), we identified 69 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs; 0.052%) and 650 INDELs (0.49%), which distributes evenly on the chloroplast genome except IR region (Fig. 1), which is congruent to the previous studies analyzed intraspecific variations of chloroplast genomes (Park et al., 2020b, 2021a). Number of the intraspecific variations displays relatively large amounts. The similar level of the intraspecific variations has been found in Pyrus ussuriensis Maxim. (121 SNPs, 0.076% and 789 INDELs, 0.49%) (Cho et al., 2019), Agrimonia pilosa Ledeb. (258 SNPs, 0.20% and 542 INDELs, 0.42%) (Heo et al., 2020), Camellia japonica L. (78 SNPs, 0.050% and 643 INDELs, 0.41%) (Park et al., 2019), Campanula takesimana Nakai (33 SNPs, 0.019% and 662 INDELs, 0.39%) (Park et al., 2021b), and Marchantia polymorpha L. (69 SNPs, 0.057% and 660 INDELs, 0.55%) (Kwon et al., 2019). However, the variations in these cases are less than those of Goodyera schlechtendaliana Rchb. f. (844 SNPs, 0.55% and 2,045 INDELs, 1.33%) (Oh et al. 2019a, 2019b) and Gastrodia elata Blume (493 SNPs, 1.40% and 650 INDELs, 1.85%) (Kang et al., 2020; Park et al., 2020a) from Orchidaceae.

The phylogenetic trees show that D. genkwa is nested within Wikstroemia, not being closely related with other species of Daphne (Fig. 2). The posterior probability of the clade of Wikstroemia and D. genkwa is significant, though bootstrap values for this relationship are not high. Stellera is strongly supported as sister to the clade in the ML and BI analysis, but it is not clearly resolved in the NJ analysis. Further sampling of Wikstroemia is necessary to clarify the relationship. The constraint analysis to evaluate the alternative hypothesis was performed using the SH and AU tests. The log-likelihood score of the constrained MP topology, which enforced a monophyly of Daphne including D. genkwa, was −74,060.01, whereas that of the original ML tree was −74,495.09. The SH and AU tests indicated that the monophyly of Daphne was not supported by the chloroplast data (p < 0.001). Thus, placement of D. genkwa with other species of Daphne is significantly incongruent with the data. Our results strongly support that Daphne as currently recognized in various taxonomic treatments (Hamaya, 1955; Ohwi, 1965; Wang et al., 1997; Oh and Hong, 2015) is a nonmonophyletic assemblage.

Maximum likelihood tree of 18 chloroplast genomes of Thymelaeaceae. Values above branches are bootstrap supports from the maximum likelihood analysis (bootstrap repeat: 1,000), the neighbor-joining (bootstrap repeat: 10,000) method, and the Bayesian posterior probabilities, respectively. Bootstrap value less than 50% is indicated with -.

The results of phylogenetic analyses are consistent with morphological (Jung and Hong, 2003a, 2003b; Lee and Oh, 2017) and preliminary molecular data (Lee, 2015). Daphne genkwa has opposite leaves with densely pubescent hairs on both surfaces and oblanceolate ovary, unusual characteristics in Daphne but common in Wikstroemia (Lee and Oh, 2017). Pollen morphology and cuticular ornamentation of leaves of D. genkwa are distinct from the other species of Daphne (Jung and Hong, 2003a, 2003b).

Our chloroplast data suggest that D. genkwa should be recognized as a species of Wikstroemia. In this case, no new combination is needed for the name of the species, as W. genkwa (Siebold & Zucc.) Domke is already available. However, it would be necessary to change the Korean genus name of Daphne, derived from the vernacular name of D. genkwa (Pat-kkot-na-mu-sok). We suggest that “Baek-seo-hyang-na-mu-sok” is suitable for Daphne, derived from the Korean name of D. kiusiana. Our phylogenetic analyses of chloroplast genomes also show that Wikstroemia is more closely related to Stellera L. than it is to Daphne, implying that Daphne is phylogenetically distinct from Wikstroemia and that the morphological similarity among some species of Daphne and Wikstroemia, such as in leaf arrangement, inflorescence, and hypogynal disk shape (Wang et al., 2007; Halda, 2001), may have resulted from homoplasy. A more detailed study of the pattern of morphological evolution in the Daphne group with more complete taxon sampling is necessary.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments, to Hwa-Jung Suh and Dong-Hyuk Lee for their help in the fieldwork, and to Yun Gyeong Choi for the assistance of laboratory work. This work was supported by the National Institute of Biological Resources under grant NIBR202005201 and the National Research Foundation of Korea under grant NRF-2020R111A3068464.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

Sang-Hun OH is Editor-in-Chief for the Korean Journal of Plant Taxonomy, but has no role in the decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.